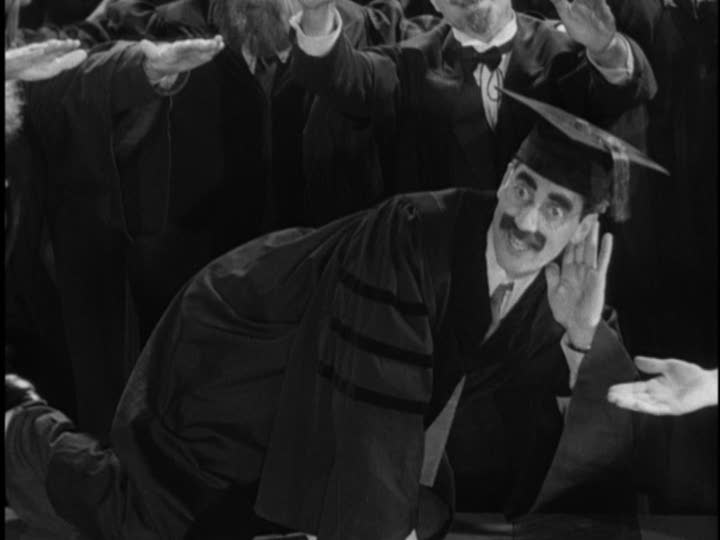

The fourth Marx brothers movie, Horse

Feathers, is a typically loopy outing for Groucho, Chico,

Harpo and Zeppo. Here, Groucho is Professor Quincy Adams Wagstaff, the

new president of Huxley College — not that it matters, since as usual in

a Marx film the plot is strictly a secondary concern. The Marx brothers

cut to the chase right from the beginning: in the first scene

Wagstaff's new presidency is announced, and his introductory speech

quickly becomes just a thin excuse for Groucho to keep riffing on all

sorts of jokes that have little or no connection to the supposed

situation. And he caps it all off with a musical number dedicated to

nihilism. "Whatever it is/ I'm against it," he sings, and leads a group

of professors in a swirling dance as he leaps up on a table, promising

to oppose whatever's normal and ordinary. And they're off, eventually

throwing Chico and Harpo into the mix as a pair of goofballs who

Wagstaff somehow manages to mistake for football players, bringing them

in as ringers to help his school defeat their rivals in the big game.

Director

Norman McLeod, who also directed the brothers in Monkey Business,

has a good handle on the quartet's manic sense of pacing and their

near-perfect interplay with one another. The film moves crisply,

careening along with barely a pause for breath. As usual, the brothers

take a variety show approach, disregarding the narrative and instead

just indulging whatever gags and performances they feel like doing:

Harpo doing one of his usual harp performances, Zeppo earnestly wooing a

vampy widow (Thelma Todd), or all four of the brothers taking turns

putting their own spin on "Everyone Says I Love You," each one offering

up their own lyrics, ranging from Zeppo's crooning balladry to Groucho's

cynical take on this romantic tune. And of course, the film is packed

with the brothers' signature wordplay, particularly between Groucho and

Chico, whose verbal dexterity always drives the Marx brothers' films.

Chico's the one who informs us that a sturgeon cuts you open when you're

sick, or that you cure a haddock with aspirin, or that he used to teach

a woman with a false set of teeth but now he teaches a falsetto, or

that you can't sleep on a football.

Chico's humor, based on such

mispronunciations and verbal puns — like a fast-paced absurdist

exchange with Harpo about hogs, pigs, hugs and picks — is a sharp

contrast to Groucho's non-sequiturs and one-liners. Whereas Chico and

Harpo seem to be perpetually caught in loops of misunderstanding and

repetitive silliness, Groucho is constantly reacting, bouncing off of

the people and things all around him, riffing on whatever he sees and

whatever anyone else says, offering up his own wry commentary on the

goofiness of others. He even makes this explicit in this film by

actually walking up the camera at one point and directly addressing the

audience, telling the viewers that they should go wait out in the

theater's lobby during what Groucho deems a tedious section, as Chico

plays the piano and sings. That's the way it always seems to work:

Groucho's the conspirator with the audience, the one who seems to be

winking at all the lunacy going on all around him, even as he gleefully

contributes to it. That's why he's perfect as the ostensible authority

figure, the university president, who actually winds up destabilizing

everything and adding to the general anarchic breakdown of order and

stability.

This is the general form of the Marx

brothers' humor: infiltrating authority and prestige with their

absurdity and their total lack of respect for the rules. In the football

game at the end of the film, Harpo gleefully subverts the mechanics of

the game at every point. There are countless shaggy-dog sports movies

where a group of misfits play a game by their own rules and come out on

top, but the Marxes exist somewhere outside that tradition, at right

angles even to that conventional depiction of anarchy. Instead, Harpo

throws banana peels at the opposing team to make them slip, which for a

while helps his team get ahead, but then he just as gleefully throws

banana peels under the feet of his own teammate before he can get a

touchdown: he's not breaking the rules to win, in other words, but

breaking the rules because that's just what he does. It's as innate as

breathing, and if sometimes his total disregard for order results in his

team coming out ahead, at other times he'll just as obliviously

contribute to his own team's setbacks and losses. Harpo, like his

brothers, isn't on any team but his own. So throughout the game he

repeatedly runs the wrong way, then leaps into a horse-drawn chariot to

take him into the end zone, then pulls out multiple footballs to pile up

the scores: he's not just breaking the rules, he's acting as if they

don't even exist, and indeed they don't seem to. No one ever questions

this absurdity; it's just accepted as the natural outgrowth of the

brothers' personalities. Nothing behaves as it should when they're

around.

At times, the anarchy of the brothers threatens to

overwhelm good taste itself, and this film includes an unfortunate

moment that betrays a more sinister undercurrent in Groucho's perpetual

quipping and joking. In one scene, Thelma Todd's character, a vamp who's

trying to seduce the brothers to get ahold of some football plays,

speaks in a squeaky baby voice to Groucho, trying to play the part of

the weak little femme to trick him into giving up his secrets. Groucho

responds by viciously mocking her, telling her that if she keeps talking

like that he'll kick her teeth down her throat. It's a startling moment

in such a lighthearted film, an ugly burst of violence and nastiness

that completely undercuts the supposedly comic tone of the surrounding

material. It exposes, too, the darker shadings of Groucho's anarchic

persona, which sometimes comes through in his cavalier disregard for

propriety and taste — like the dismal way he treats Zeppo, who plays his

son here. There are times when Groucho's wit and patter reveal that

when you strip away order and stability, some rather ugly things escape

along with all the humorous absurdity.

But that's the essence of a

Marx brothers film: the breakdown of order. Even the film itself often

seems to be breaking down around them. The film was censored and chopped

of its bawdiest lines, and in its existing form it's a patchwork

assembly that only exacerbates the anarchy and roughness that generally

characterized the Marx movies. There are inexplicable cuts and splices

in the film, the visible remnants of excised sequences or lines, and

this splicing lends a herky-jerky quality to the film at points. In one

scene, the ragged cutting makes Groucho seem to move without regard for

the laws of physics, leaping across time and space as though he had been

cut loose from reality as we know it. Groucho kicks Zeppo out, and as

the door slams shut, there's a cut that replaces the slamming door,

making the door shut on its own and Zeppo disappear. Before this

disjunction can even be processed, the camera is following Groucho as he

hunches down and runs across the room, grabbing a lantern from a nearby

table. Then he's abruptly at the window, making a quip before another

jump cut leads into him running towards the camera. Then he's leaping

over a couch to stand next to Thelma Todd, and another jump cut

transitions into him hopping into her lap.

This disjunctive

editing is a sign of the film's looseness and roughness, its casual lack

of concern for continuity or reality. Groucho especially seems to exist

somewhere outside of reality as he catapults across the room, the jerky

rhythms of the cuts enhancing his naturally stylized movements. As he

duck-walks and stutter-steps, the film seems to be syncopating off of

Groucho's own inbuilt rhythms, erasing whatever's not strictly

necessary, stripping away everything but the essence of Groucho. At one

point, he starts to say "where were we" but only gets out the "where"

before the rest of the frames are elided, and he seems to instantly leap

onto the couch again, answering himself, "oh yeah." That's it in a

nutshell: there's only as much as is needed for the gag, and the rest is

crudely sliced away. It's an accident of the film's troubled censorship

history and the corrupted form in which it has survived, but it only

enhances the film's lackadaisical economy. Horse Feathers is a

typically nutty, loose-limbed effort from the Marx brothers, capturing

their antics at their most hilarious and profane.

Horse Feathers

GODOF- Admin

- عدد المساهمات : 10329

نقــــاط التمـــيز : 61741

تاريخ التسجيل : 08/04/2009

العمر : 33

لا يوجد حالياً أي تعليق