The End of Summer was

Yasujiro Ozu's penultimate film, and it's thus perhaps fitting that the

film's subject, at least in part, is the end of life: the English title

refers not only to seasonal changes but to pivotal moments in life,

particularly its cessation. (The Japanese title, literally translated as

Autumn for the Kohayagawa Family, conveys the same sense of

some doors closing while others open anew.) The elderly Kohayagawa

(Ganjiro Nakamura) has had a full, busy life, and now that he's near its

end, he wants only to squeeze out the last few drops of pleasure from

his existence, and to leave this world believing that his family is

going to be taken care of after he's gone. He doesn't dwell on death or

show any overt signs of preoccupation with what happens after he's gone,

but it nevertheless clearly motivates him. In particular, he wants to

know that his daughters — young, unmarried Noriko (Yôko Tsukasa) and

widowed Akiko (Setsuko Hara) — are settled and married. His eldest

daughter, Fumiko (Michiyo Aratama) is already married, to Hisao (Keiju

Kobayashi), and for them Kohayagawa wants to know that his perpetually

struggling business, which he's more or less passed on to Hisao, is

well-maintained. Still, although Kohayagawa is in some ways getting his

affairs in order and tying up loose ends, he's hardly given up on life,

and he retains the sense of pleasure he feels in the company of Sasaki

Tsune (Chieko Naniwa), who he'd had an affair with many years before and

with whom he'd rekindled this affection in his dotage. He is an example

of one end of the see-saw dichotomy that runs through so much of Ozu's

work: the tension between personal happiness and the stability of the

family or the larger community. It is the tension between the individual

and the group, here realized as Kohayagawa's balance between doing what

he wants and doing what his family, who are embarrassed of his

philandering and his carefree lifestyle, would prefer.

This is a

recurring topic in Ozu's films, many of which involve the kinds of

marriage dramas that Noriko and Akiko face, in which the women must

choose between the option that will make them happiest, and the option

that will make their families happiest and most stable. Noriko and Akiko

are both being set up with men who bemuse and entertain them but who

they certainly don't love. Noriko, in fact, is in love with another man,

a man who she worked with but who moved away before they could truly

express their feelings for one another. Akiko, for her part, would

prefer to remain a widow, raising her child by herself, rather than get

married again. But both women nevertheless are seriously considering

these arranged marriages for the sake of their family. The film's drama,

quiet and understated as it is, revolves around the sisters' crucial

choice between their individual happiness and their reluctance to

disappoint or inconvenience their family. It's a plot Ozu returned to

again and again, as he probed the changing dynamics of Japanese culture

post-World War II, the infusion of Western influences, and the friction

between old ways of doing things and new understandings of the

possibilities open to individuals outside of traditional group

structures.

Ozu's gentle aesthetic — static shots from a fixed,

low perspective, arranged in patient rhythms — is perfectly suited to

such introspective stories. He intersperses his inter-generational

narrative, as usual, with unpopulated interludes, shots of these

domestic settings denuded of their inhabitants. These interludes are

lyrical poems, often three-line poems in which each "line" is an

individual shot. These triplets serve multiple purposes for Ozu: they

are dividers between dramatic, narrative, dialogue scenes; they

establish a sense of place; they influence the film's rhythm and pacing;

they enhance the impression that Ozu is a sublime documenter of

everyday life in all its minutest details. But most importantly, these

images are simply sensual and sensory, almost abstract in their oblique

relationships to the narrative scenes.

Sometimes the syntax of these "poems" is

clear enough: start with a medium shot of an empty room, then cut to a

closeup of a pale blue lantern, a detail from the wider shot. That's a

standard enough gesture. More unpredictable is Ozu's penchant for

offering unusual angles on the same scene. The three shots shown above

are a typical example of one of Ozu's poetic sequences: three views of

wooden baskets lined up along a wall, but the relationship between the

three shots is ambiguous and formal rather than straightforward. The

first two shots rhyme against one another with opposing angles and

slightly altered distance, together forming an uneven upside-down "V"

shape, while the third shot unexpectedly pulls back down an adjacent

alleyway. This shot sequence is mysterious and purely formal, a

diversion from Ozu's documentation of his ordinary characters to examine

the rich details and prosaic beauty of their surroundings. This

particular tendency in Ozu is perhaps his most characteristically

Japanese touch, derived from a rich tradition of such visual poetry,

like Hokusai's famous "views" of Mount Fuji, each one drawn from a

different angle and infused with different hues.

The film's

opening sequence provides a stunning example of how Ozu's patient

cutting from one static shot to another can subtly lead into the buried

drama of his stories, as well as creating an overpowering mood through

the rhythmic editing. The first two shots show the city of Osaka at

night, its blinking neon lights and tall, dark skyscrapers instantly

announcing the modernity of the setting. Ozu then cuts to a shot in the

interior of a bar, looking from his typical low angle down a row of bar

stools at the blinking neon sign out the window and the bar patrons

sitting at the counter. The next shot is a two-shot of a man sitting at

the bar with one of the hostesses, and then Ozu cuts to single shots of

each of them in turn. It's a simple rhythm, but in just six shots Ozu

has moved fluidly from the broadest possible context to the most

intimate, from images of an entire city to closeups of individuals. His

deliberate aesthetic creates a cumulative effect, with each shot adding

to the mood established by the earlier shots; the intrusion of Setsuko

Hara, as the traditional woman Akiko, into this modern world is

especially startling, with her traditional garb clashing against the

bright, stylish dresses and American-style makeup favored by most of the

younger girls in this place.

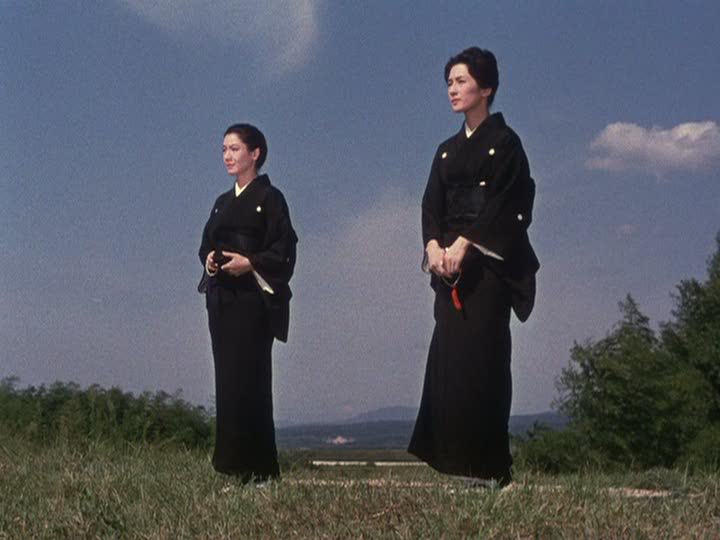

All of this slow accumulation is

leading towards a moving, complex denouement, in which Akiko and Noriko

make their respective decisions as the older generation cedes its reign

to the younger ones. The film's entire final act is comprised of Ozu's

epic depiction of a funeral, a lengthy and emotionally intense sequence

spread out across multiple different locations. His editing rhythms take

on a sublime purposefulness at this point. A pair of peasants by a

river are surrounded by crows, a harbinger of death, and they look up at

the tall chimney of the nearby crematorium, which will emit clouds of

smoke at the climax of the funeral. The peasants exchange pat clichés

about the "cycle of life" and death as the passing of the torch from one

generation to the next, but Ozu makes these values apparent more

poignantly in his visuals, and in the more indirect conversation between

Akiko and Noriko. The two sisters watch the smokestack from a nearby

hillside, discussing their respective decisions and the importance of

being happy in life. Meanwhile, the remainder of the family gathers in a

restaurant for the funeral lunch, and though they chatter on about life

and death, sometimes cheerful and sometimes distraught, the moment when

they first see the crematorium's smoke is entirely silent, shot from

behind, with one woman slowly rising to watch and the others solemnly

following, until everyone is arranged at the window in a tight group,

watching the last fragile wisps of a life being blown away by the wind.

The film ends with another of Ozu's poetic interludes, on the subject of

death this time: crows under a pier, crows on a sand bank, crows

hopping from one grave marker to the next, cawing, their black feathery

forms seeming like negative space against the pale blue of sky and water

or the lush greens of the foliage.

What's especially unexpected about The

End of Summer, given its big themes and serious subjects, is how

light it is in its approach. Ozu's comedy is often broader and airier

than one would expect from an artist of his general delicacy and

deliberateness. In one scene, Akiko's would-be new husband pulls out a

cigarette lighter that unleashes a massive flame, so that the act of

lighting a cigarette is like sticking one's face into the path of a

flamethrower; it's a gag of visual incongruity on par with Quentin

Tarantino's recent pipe gag in Inglourious Basterds (and that's

probably one of the few times you'll see anyone link Tarantino and Ozu

in any way). More importantly, Ganjiro Nakamura in particular delivers a

wonderfully comic performance as the family's spry, cheerful patriarch.

When he walks through the streets, fanning himself to shield against

the oppressive heat, there's a faint bounce in his step, a peculiar

waddle that Ozu synchronizes with the jaunty soundtrack. There's great

comic charm in Kohayagawa's attempts to elude his family so he can visit

his mistress. At one point, while playing hide-and-seek with his

grandson, he pretends to be looking for the boy but is actually

stealthily dressing and preparing to go out. Sasaki, his mistress,

provides some wry humor as well, particularly in her relationship with

her daughter Yuriko (Reiko Dan), who she claims is Kohayagawa's daughter

even though the girl's parentage is by no means certain. These two

women are matter-of-fact gold-diggers, getting the most they can out of

their relationships with men, but Ozu doesn't judge them harshly: they

simply do what they have to in order to get by, to survive and

experience some measure of happiness in their lives. Like Kohayagawa

himself, they take life as it comes and enjoy it as much as possible.

Despite Ozu's sympathies for older ways of doing things, for the bonds

of tradition and duty and responsibility, it's apparent that he

appreciates this more lackadaisical approach to life as well.

The

End of Summer is a beautiful, graceful film, a resonant work that

frankly addresses mortality and the shifting cultural status quo. It is a

profoundly unhurried film, and yet there is an economy of gesture and

movement in Ozu's aesthetic that makes the film seem very condensed.

Each movement has a purpose: there are several shots in which two people

sit into a crouching position together, their movements perfectly

synchronized, as though they are both attuned to the world's invisible

rhythm. This rhythm, so subtle and yet so powerful, is the rhythm of

Ozu's films: slow, graceful, perhaps slightly melancholic, but also at

times joyful and even exuberant, quietly exulting in the possibilities

of the future or even just the sunny warmth of one of the final summer

days before autumn.

لا يوجد حالياً أي تعليق