40. Y: THE LAST MAN

by Brian K. Vaughan, Pia

Guerra, Goran Sudzuka, etc., 2002-2008

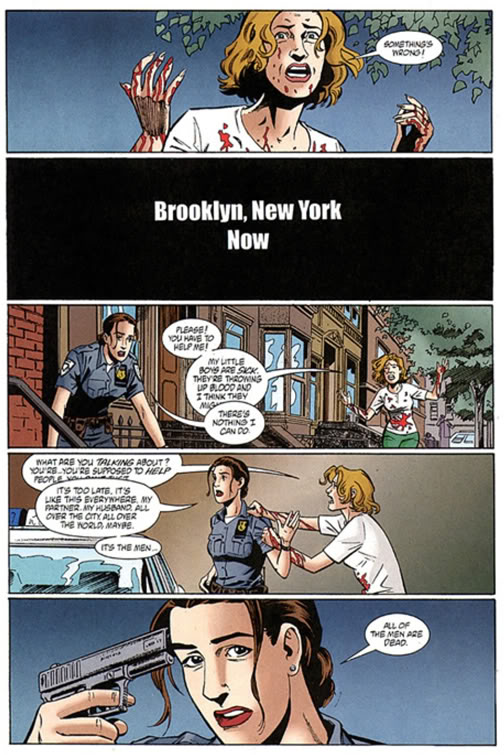

Brian K. Vaughan's Y: The Last Man is

Brian K. Vaughan's Y: The Last Man is pulp storytelling at its best. Starting from a winner of a high-concept

premise — a plague wipes out all the males on earth save two, the young

slacker Yorick Brown and his misbehaving pet Capuchin monkey — Vaughan

explores the various repercussions of this apocalyptic scenario in one

exciting, probing story after another. The book wears its politics on

its sleeve, and its commentaries on gender, war, race, religion and

politics are almost always blunt and on-the-nose. But Vaughan gets it

across because he just has such an instinctive feel for genre

storytelling, and for characterization over time. Yorick and the

increasingly large cast of friends and enemies surrounding him are

memorably developed over the series' length. Vaughan's issue-to-issue

plotting is impeccable, and the story moves with the page-turning drive

of the best pulp fiction. It's almost impossible to put down once you

start reading. In this respect, the clean, attractive art of co-creator

Pia Guerra (and a string of mostly strong guest artists and substitutes)

does just what it should, defining the characters with a few bold

strokes and clearly underlining Vaughan's storytelling. There's nothing

showy or innovative about this series, just good classical storytelling

within a light sci-fi framework. Vaughan earns extra points, too, for

his bold final arc, in which he abruptly shifts the series' focus in

surprising ways to deliver a strange, emotionally intense, utterly

unforgettable coda, the kind of ending that hits like a ton of bricks

because no one ever saw it coming and yet, in retrospect, it's an

utterly perfect conclusion.

39. SEXY VOICE AND ROBO

by

Iou Kuroda, 2000-2003

Iou Kuroda is part of that small corner of the

Iou Kuroda is part of that small corner of the Japanese comics industry that is analogous in some way to the American

independent or art-comics scenes: working outside of mainstream genres,

with a distinctive and decidedly unpolished style, publishing outside of

the biggest venues. Sexy Voice and Robo is a collection of

Kuroda's short stories starring the titular Sexy Voice, a

fourteen-year-old girl who earns her nickname by posing as an older girl

for a phone line where guys call in to talk, non-sexually, with what

they think are attractive young women. Sexy Voice is preparing herself

for a life as a spy, or something equally exciting and glamorous, so

she's training herself to act, to be deceitful, and getting herself

involved in all sorts of shady business. She becomes an errand girl for

an aging mobster, and occasionally ropes in the pathetic toy collector

Robo, one of her regular phone line contacts, to serve as an ineffectual

bodyguard on her more dangerous outings. Kuroda's stories, however, are

less action-packed genre pieces than quiet, reflective examinations of

communication, relationships, memory, the gaps between appearance and

reality, and the unknowability of the inner self. Throughout it all,

Sexy Voice is an endlessly fascinating and charming heroine, overflowing

with wit and vivaciousness, caught at a moment halfway between a

playful kid and the jaded adult she might someday become. Kuroda's thick

linework, so sketchy and so unlike most other manga, is perfectly

suited to these unusual, appealing stories, which mix genre elements

with an observational affinity for the little things that comprise

character.

38. LIKEWISE

by Ariel

Schrag, 2009

For every year of high school, from 9th grade

For every year of high school, from 9th grade through 12th grade, Ariel Schrag set herself the task of writing a comic

about her experiences. This four-book journey culminates with Likewise,

the chronicle of Schrag's 12th grade year, a 300+ page opus that

transforms this high-schooler's largely internal dramas into a

stylistically diverse stream-of-consciousness epic. The book ranges far

and wide, continually shifting from the recounting of events and

anecdotes to more conceptual segments where Schrag wrestles with

understanding and defining what it means to be a lesbian, or how to get

over her long-time crush and one-time girlfriend Sally, or why she

documents all this stuff in the first place and what it all means. She

frequently namechecks James Joyce's Ulysses, and adapts his

stream-of-consciousness style to a high school girl's sense of media

overload and diaristic rambling. Schrag's voiceover is a near-constant

presence in caption boxes throughout the book, sometimes representing

the transcriptions of journal entries, sometimes pages of computer

printouts, sometimes tape recordings of conversations and monologues.

Her art style is as diverse as her continually morphing prose, too. Her

sketchy, expressive figures, with their rubbery faces, sometimes

solidify into more densely rendered sequences with delicate shadings, or

into pages where rich blacks dominate the compositions, or others where

the characters and words seem to be disintegrating into childlike

scribbles of great emotional intensity. Throughout it all, Schrag's

self-awareness and self-criticism mediate the excesses of her

autobiographical indulgence, preventing the book from seeming like the

mere teary ramblings of an introspective teenager. By the same token, Likewise

is infused with a real sense of humor and observation that pushes

Schrag out of herself, forcing her to engage with other people, to

include their perspectives in her work to offset her own. It's a dense,

rewarding book that transmutes high school melodrama and theatrics into

something far richer.

37. LOST GIRLS

by

Alan Moore & Melinda Gebbie, 2006

This infamous book is Alan Moore's foray into

This infamous book is Alan Moore's foray into literary pornography, as he retells the stories of popular fantasy

figures Dorothy, Wendy and Alice as sexual adventures, recounted through

the lens of nostalgia on the eve of World War II. Melinda Gebbie's

sumptuous, quirky artwork lends depth and nuance to Moore's deliberately

purplish prose, while the book's themes are much deeper than one would

expect from Moore's stubborn insistence that he was making straight-up

porn. The book deals with differentiating reality from fantasy, and

encouraging imagination as a creative outlet, an escape and a counter to

the horrors of reality. It is, in fact, a slap in the face to those who

would censor artistic expression. Moore issues challenge after

challenge to the puritanical and perverted minds who insist that to look

at, or draw, a morally objectionable act is the same as actually

engaging in it. It's a beautiful, provocative work.

36. BLACK HOLE

by

Charles Burns, 1993-2004

Charles Burns' long-running series Black Hole

Charles Burns' long-running series Black Holeis the peak of the artist's great career in horror comics. Burns has a

knack for locating pathos and unsettling emotions in horror scenarios,

and this story about a sexually transmitted plague among small-town

teenagers is no exception. The series ran throughout much of the 90s,

but since Burns finally published the last few installments and the

collected book after the turn of the millennium, presenting it in its

long-awaited definitive form, it seems appropriate to count it among the

best books of the 2000s. Burns' noirish style is well-suited to this

unsettling story, in which teenage anxiety about sexuality is

externalized in the form of various mutations that turn affected teens

into monstrous creatures, their sexual anguish etched into their bodies

as scales, boils, rashes and new appendages. Few books do a better job

of capturing the fear, and the excitement, of nascent desire and

adolescent longing, as these diseased teens are driven mad by hormones

and embarrassment.

35. ALIAS

by Brian

Michael Bendis & Michael Gaydos, 2001-2005

Before Brian Bendis began turning his attention to

Before Brian Bendis began turning his attention tovarious Marvel superhero titles, with increasingly diminishing returns,

he crafted the masterful series Alias, which existed on the

periphery of the Marvel universe and dealt with superhero storytelling

in an unusual and emotional way. The series centers on Jessica Jones,

who is at least technically a superhero, or was at one time anyway: she

has some minor powers, a bit of super strength, and once dressed up as a

crimefighter. Now, however, she's settled into a more prosaic life as a

private detective, where her powers occasionally come in handy, but

mostly she's just a normal, if tough and isolated, woman. What sets this

book apart — beyond its presence in Marvel's MAX imprint, which allowed

it greater leeway in cursing and sexuality — is its focus on character

development over action. Jessica is a strong, complicated character, and

the throughline of her growth throughout this book is the real focus

rather than the genre plots. Bendis' most brilliant ploy is to use

superhero melodramatics as a way of probing character in unexpected

ways: Jessica's long-ago encounter with the Purple Man becomes a central

device in a surprisingly candid, sophisticated story arc about dealing

with sexual abuse and humiliation, while her romantic relationships with

superheroes Ant Man and Luke Cage are developed far beyond the usual

level of so-called love in superhero comics. The book deals

intelligently with issues of trust, insecurity and painful memories, and

Jessica is surely one of the most memorable and original female

characters in all of superhero comics.

34. PLUTO

by Naoki

Urasawa, 2003-2009

Naoki Urasawa's Pluto is the manga-ka's

Naoki Urasawa's Pluto is the manga-ka's response to his biggest influence, Osamu Tezuka, the single artist who

has arguably had the greatest effect on modern Japanese comics. Urasawa

takes as his reference point a popular story from Tezuka's long-running Astro

Boy series, a sci-fi adventure mostly aimed at younger readers and

probably the artist's most famous creation. "The Greatest Robot on

Earth" details Astro Boy's struggle against a mysterious and powerful

robot called Pluto, who's destroying all of the most powerful robots in

the world in a quest to be the best. Urasawa expands upon this story,

using Tezuka's original creation as a framework within which he builds

his own much more complicated world, filling in details and fleshing out

the characters with motivations and histories that were barely even

hinted at in Tezuka's breezy, action-oriented tale. Pluto

shifts the focus onto robot detective Gesicht, who's investigating a

series of murders that may be connected to the systematic destruction of

the world's most powerful robots. Urasawa weaves in references to

contemporary events, including some surprisingly blunt "war on terror"

satire and minimally camouflaged references to Iraq, but his real

innovation here lies in the way he digs beneath the surfaces of these

characters, unearthing emotions and philosophical questions that cut to

the core of what it means to be human, to think and feel and regret and

love and hate. Even more than Urasawa's long-running thriller Monster,

the real thrust of this much more compact series is an interrogation of

the concepts of nature versus nurture, examining the events and

experiences that define a person's personality and moral character.

Urasawa is always interested in evil, which he sets up as a terrifying

absolute only to probe the more subtle gradations between good and evil:

in Urasawa's work, everyone has their reasons for what they do,

everyone has their secret traumas and tormented memories. It's a pulpy

soap opera convention that Urasawa routinely imbues with much greater

depth, lending pathos and philosophical sharpness to his propulsive

storytelling.

33. LOUIS RIEL

by

Chester Brown, 1999-2003

Chester Brown's biography of Canadian dissident

Chester Brown's biography of Canadian dissident Louis Riel is a strange and inscrutable work, presenting Riel's tragic

story in a simple, direct style, with little trace of commentary, so

that it's difficult to know what to make of this tale: is it a satire, a

tragedy, a black comedy, an exploration of spirituality? Or none of the

above? Is it simply the story of a life, told in such a way that all

the external interpretations, the guesses and conjectures and the weight

of history, simply fade into inconsequentiality in the face of Brown's

blank-eyed, Harold Gray-inspired style? Riel, for Brown, is simply a

man, and when confronted with the unknowability and distance of such an

extraordinary but obscure man, Brown sticks to the facts without

venturing into more ephemeral areas. The result is an attempt at an

"objective" biography that raises many more questions than it even

attempts to answer; Brown tried the same thing with Jesus in his Gospel

interpretations, with even more confusing and provocative results.

32. A DRIFTING LIFE

by

Yoshihiro Tatsumi, 2009

The quiet, introspective manga of Yoshihiro

The quiet, introspective manga of Yoshihiro Tatsumi was introduced to American audiences by Drawn & Quarterly's

series of hardcover tomes collecting some highlights from Tatsumi's

punchy, minimalist short stories. With his simple, direct style and

schlumpy everyman protagonists, Tatsumi depicted urban malaise,

loneliness and sexual perversion with a flat, affectless tone that

contrasted against the sometimes harrowing content of his stories. But

as good as these stories are, his magnum opus is a newly produced,

massive volume that tells the story of his early years as a struggling

manga artist, trying to create a new, more realistic movement within

Japan along with a few likeminded artists. It is a memoir of a largely

unexplored area of Japanese comics, packed with references to artists

and works that are largely unfamiliar in the US. His straightforward

style positions this volume as a historical account, establishing the

context of this time and place both in relation to Japanese history

(World War II, the American occupation, the bombs) and the artist's

personal life. It is, typically, concerned with sexual maturity, and

also with the internal struggles of a man trying to find his own place

in life and art. It is especially enlightening to see Tatsumi himself,

through his thinly veiled autobiographical stand-in, assume the place of

his usual everyman protagonist, confirming the artist's sense of

identification with his troubled, conflicted male antiheroes.

31. MADMAN ATOMIC COMICS

by

Mike Allred, 2007-2009

Mike Allred's periodic returns to his defining

Mike Allred's periodic returns to his defining creation are always cause for celebration. Frank Einstein, the

reincarnated hitman known as the Madman of Snap City, had previously

been the star of three different series, but the last one, Madman

Comics, ended in 2000, and Frank's guest spots in Allred's

enjoyably fluffy spinoff The Atomics weren't quite as

satisfying. Madman Atomic Comics reunites Allred with his

signature character, who looks like a superhero but more often acts like

a goofy, lovestruck kid, or maybe a philosopher. Indeed, this fusion of

childlike enthusiasm and philosophical speculation is the core of Madman,

which recycles 60s comics and pop culture tropes without the irony and

deconstruction that so often accompanies modern attempts to reinvigorate

the culture and kitsch of the not-so-distant past. Allred's characters

speak in a hip patois of beatnik lingo, "groovy" 60s hippie-speak and

slangy comic patter. His clean, pop-art drawing style reflects a similar

blend of eras and influences, a blend that at times explodes to the

surface within the pages of this latest series, which perhaps represents

the peak of Allred's Madman saga thus far. The series opens

with Frank in unfamiliar territory, briefly becoming convinced of his

own godlike status before heading off on a twisty odyssey that mostly

involves coming to terms with his own past, identity and existence as a

creative product. In the series' epic third issue, Allred sends Frank

careening through a shifting mental landscape where each individual

panel is drawn in a different style from the history of comics. Thus,

Allred gets to have great fun envisioning Frank (and his robot

doppelganger Astroman) as drawn by a who's who of comics' greatest

stylists: Caniff, Crumb, Herrimann, Schultz, Segar, Gottfredson, King,

Seuss, even encompassing more obscure indie names like Richard Sala and

Chester Brown, alongside various superhero and EC Comics pastiches. It's

a dense, fun issue, propelled as much by the constant stream of

inquisitive, philosophical dialogue (all about the self and the nature

of life) as by the stylistic diversity on display. This is the apex of

Allred's latest take on his creation, perhaps, but it's also indicative

of the strengths of this series as a whole, its careful balance between

dazzling visual ingenuity and the more subtle emotional and intellectual

concerns that occupy the minds of Frank and his creator alike.

30. EPILEPTIC/BABEL

by

David B., 1996-2003/2004-2006

The French cartoonist David B. wrote and

The French cartoonist David B. wrote and published much of his epochal series Epileptic — an

autobiographical story about his relationship with his increasingly

non-functioning epileptic brother — during the 1990s, but he finished

the work and published it in English for the first time during the

2000s, which in some way qualifies it for this list. It is, in any case,

an immensely satisfying work, because it doesn't make the mistake of so

many autobiographical comics of thinking that a true story is enough.

Instead, David B. takes his youth and his brother's ailment as the raw

material for his wide-ranging attempts to understand the concepts of

sickness, family, history and maturity. With his elegant style,

dominated by striking blacks and contrasts, he invents numerous

metaphors and visualizations for his brother's disease, treating the

fight against the disease as a physical, mortal conflict.

David

B. then continued his work in Babel, a thus-far incomplete

series that elaborates upon the territory of Epileptic by

venturing further into political, historical and philosophical content

in the context of his family and his youth. This series' examination of

genocides and wars brings a global, historically engaged perspective to

the artist's affecting visuals.

29. CHIMERA #1

by

Lorenzo Mattotti, 2006

Italian artist Lorenzo Mattotti has not been a

Italian artist Lorenzo Mattotti has not been a particularly prolific presence in comics, though his short albums of the

80s — Fires, Murmur, Labyrinthes —

established him as a fine, expressive artist with an intuitive grasp of

color. Chimera is thus a rare pleasure from this elusive

artist. Drawn for Fantagraphics' Ignatz line and intended to be the

first issue of a continuing series — which, true to form, now seems

unlikely to materialize — Mattotti's Chimera is a

semi-abstract, mostly wordless comic in which multiple styles collide

against one another. The book ranges from sketchy, scruffy pen drawings

to thick ink washes to passages of dense, frenzied linework. Mattotti

captures the flow of dreams and nightmares, fluidly transitioning

between layers of reality as his chameleonic style shifts from spacious

compositions dominated by white space to dark passages where you have to

squint into the inky complexity to suss out the nuances at work within

Mattotti's roiling chaos. The book ends with its best sequence, a

panel-by-panel journey into a dark, shady forest that hints at a next

issue that never was. It would've been great if this series had led

somewhere further, but as it is this comic stands alone as a powerful

work in itself.

28. DOGS AND WATER

by

Anders Nilsen, 2004

Dogs and Water is the most complete and

Dogs and Water is the most complete and potent statement thus far from promising young cartoonist Anders Nilsen,

who has created a small but intriguing body of work ranging from his

in-progress series Big Questions, to his harrowing attempts to

respond to the death of his fiancée in The End and Don't Go

Where I Can't Follow, to his two books of ultra-minimal sketchbook

exercises, to his various anthology appearances and short-form

experiments. In Dogs and Water, his talent is at its most

concentrated and distilled, creating a simple but enduring work whose

resonances and themes lie just beneath the placid surface. With his

minimal line and judicious use of white space, Nilsen sketches out a

forlorn wasteland where a solitary wanderer drifts along, encountering

various horrors along the way. The book is a parable of wartime

dislocation and dehumanization, a mostly wordless story where

communication is difficult but ultimately offers the only hope of

salvation for these disconnected, isolated people.

27. THE DARK KNIGHT STRIKES AGAIN

by

Frank Miller & Lynn Varley, 2001-2002

Frank Miller's sequel to his widely acclaimed The

Frank Miller's sequel to his widely acclaimed TheDark Knight Returns is not thought of with much respect or

affection by most comic fans. Fans expecting another DKR, a

second gritty look at a tough, grizzled old Batman coming out of

retirement, instead got a garish, outrageous media/government satire in

which the titular Dark Knight barely even appears for long stretches of

time. The book is as much Miller's snotty perspective on the DC universe

in general as it is a return to his apocalyptic Batman universe, as he

satirizes and pokes at the company's most iconic heroes: Superman,

Wonder Woman, Green Lantern, The Question, Robin. It's probably the

nastiest and ugliest work to ever come out of the Big Two's superhero

factories, but there's also a kind of gaudy grandeur to Miller's vision,

particularly in the computer colors of his then-partner Lynn Varley.

Her work on Miller's sketchy, minimalist compositions often goes well

beyond mere coloring into actually creating the Vegas-like infotainment

superhighway in which this story is set. It's a messy book, no doubt

about it, inflected with Miller's loony right-wing paranoia and his

naked contempt for the characters he's writing about, but in spite of or

maybe because of these out-there tendencies, this book is never less

than a visceral, entertaining, balls-out read, from its frenzied opening

to its cheekily anti-nostalgic ending.

26. THE SQUIRREL MOTHER

by

Megan Kelso, 2001-2006

Megan Kelso's short stories are quiet and

Megan Kelso's short stories are quiet and unassuming things, drawn with a clean, breezy style and unadorned

dialogue. It would be easy to dimiss these fragile, open-ended pieces,

collected in her anthology The Squirrel Mother, as simple and

overly familiar tales of the mundane, except that Kelso's moral probing

and feel for understated emotions goes far beyond the talents of most of

her peers. The deceptively clean style and pastel colors suggest a

light read, but Kelso's work can be devastating in the way she pares

down the excess to get at the essence of a particular moment or

situation, like a mother's struggle with domestic responsibility versus

personal ambition in the title story. In the book's moving and

mysterious final story, another woman, this one a rural pre-teen, plays a

sexual game, her reasons unexplained: because there's nothing better to

do, or she's insecure, or she just finds it fun? These kinds of

decisions and feelings are at the core of Kelso's complex, emotionally

challenging comics.

25. GYO

by Junji Ito,

2001-2002

The work of horror manga-ka Junji Ito is marked by

The work of horror manga-ka Junji Ito is marked byhis strong, unusual imagination, his knack for concocting devilishly

bizarre scenarios and extracting horror from absurdity. Nowhere is this

more evident than in the two-volume Gyo, which starts from a

bizarre premise — decaying fish begin to sprout robotic legs and take to

the land — and just gets weirder and weirder from there. There's an

element of gross-out, top-this grotesquerie to Ito's precisely drawn

images, and he follows each of his nutty ideas through to its

(il)logical conclusion. By the time the book ends, it's gone a long way

from the jaunty disjunction of its sharks-with-legs opening premise, and

the wealth of bizarre, terrifying sequences along the way make this one

of modern horror comics' best works.

24. MULTIFORCE

by Mat

Brinkman, 2000-2005

Mat Brinkman's Multiforce is quite

Mat Brinkman's Multiforce is quite possibly this elusive artist's defining work, consisting of a series of

newspaper-format strips mostly published in the Paper Rodeo

zine. These large-format single-page pieces are perfectly suited to

Brinkman's feverish, incredibly detailed visions of a strange world

populated by monsters, skeletons, and outlandish creatures of all kinds.

His strips are funny and bizarre, packed with numerous sight gags (a

skeleton head rolling down a complex series of paths, then bursting open

to unleash a rainbow stream) and absurdist comic dialogue. Monsters

sell arms on a street corner and the constant back-and-forth wordplay

and banter make it uncertain if they mean weapons or actual limbs. A

skeleton walks everywhere repeating his name as though he's terrified of

losing his sense of identity, but his constant self-identification

proves to be his fatal undoing. Brinkman's dense pages are filled with

small stories and gags like this. He also works with radical shifts of

scale, as his panels vary from tiny little clusters of miniature figures

to massive landscapes that take up half a page. Multiforce is,

along with Brian Chippendale's Ninja, one of the great

statements to come out of the loose Fort Thunder artist's collective, an

encapsulation of Brinkman's imaginative, fantastical aesthetic in a

handful of large, dense pages.

23.

GOGO MONSTER

by Taiyo Matsumoto, 2000

Taiyo Matsumoto, most famous for his cyberpunky

Taiyo Matsumoto, most famous for his cyberpunky magnum opus Tekkon Kinkreet, returns again to the subject of

rebellious young boys in GoGo Monster. This book, originally

published as a single volume in Japan in 2000 and only recently making

the transition into English, is mainly focused around an outcast boy

named Yuki, who is in touch with an alternate world of monsters and

powerful godlike beings that only he seems to see. He shuns his peers

and his ordinary world for this fantasy realm, and his gradual shift

towards adulthood, when he begins to lose touch with this alternate

world, is symbolized by the arrival of a new gang of more threatening,

sinister monsters who begin to overwhelm and battle with Yuki's old

friends. Implicit in this story is a clever metaphor for maturing, for

growing up and losing touch with the vivid imagination and playfulness

of childhood, which are replaced with more adult concerns about

mortality and responsibility. Yuki is a boy who's afraid to grow up, and

Matsumoto dramatizes and visualizes his anxiety in terms of an epic war

between invisible monsters who live in water drops and dance to the

sound of the boy's silver harmonica. Yuki is joined in his struggle by

his new friend Makoto, a more grounded boy who is nevertheless drawn to

Yuki's strange immersion in unseen worlds, and by the outcast known only

as IQ, a boy so isolated from the world that he goes everywhere with a

cardboard box covering his head, so that he only looks out at his

surroundings through a small circular eyehole. Matsumoto's affection for

these outcasts and dreamers is strong, and his own eccentric, sketchy

style, so unlike most other manga, is perfectly suited to this kind of

story. His ragged linework and skewed, constantly shifting perspectives

contribute to the book's sense of a slippage between prosaic reality and

some more magical realm whose presence is sensed in subtle ways rather

than seen.

22. HOW TO BE EVERYWHERE

by

Warren Craghead III, 2007

Warren Craghead's work is quite distinct from

Warren Craghead's work is quite distinct from traditional comics, and this compact book — featuring Craghead's

responses to the poetry of Apollinaire — is the perfect introduction to

his experimental, evocative style. Craghead weaves Apollinaire's words

into assemblages of minimalist drawings, most of which show fragmentary

views of people and objects: an arm, a hat, a ladder, a leg, a face with

no features. These fragments are arranged into complex structures on

pages that use white space in striking ways. Craghead's compositions

force slow, careful reading, following the unconventional flow of the

words around the page, and tracing the ways in which these words — which

are used as graphic elements as much as the drawings themselves —

interact with the images.

21.

OMEGA THE UNKNOWN

by Jonathan Lethem & Farel Dalrymple,

2007

Novelist Jonathan Lethem's "cover version" of a

Novelist Jonathan Lethem's "cover version" of a compromised 1976-77 Steve Gerber/Mary Skrenes/Jim Mooney superhero

series is a brilliant and imaginative take on superheroes made by

someone who clearly loves them and sees the untapped emotional potential

in the genre. Lethem's version of the story starts from the same ground

as Gerber's series; his first issue is virtually a beat-for-beat remake

of the original's first issue, in which a detached, intellectual young

boy gets in a car accident, discovers that his parents were actually

robots, and manifests strange powers after coming into contact with a

blue-clad, silent superhero type, the titular Omega. From there, Lethem

increasing departs from the original story, which was compromised by

Marvel's insistence that Gerber incorporate multiple Marvel Universe

guest stars and tell a more conventional superhero story than he'd been

planning. Lethem, on the other hand, is free to explore his weirdly

unlikable young hero and the resonances of the story's Hell's Kitchen

setting. Lethem's typical concerns — community, race, the power of

fantasy, corporate branding versus individuality — percolate throughout

this story, even as it veers back and forth between a loose

superhero/media satire and a nuanced coming-of-age drama. There's a lot

going on here, and Dalrymple's sketchy, distinctive art, bolstered by

the muted color palette of Paul Hornschemeier, breathes life into this

quirky universe. Hornschemeier himself also draws a superhero origin

story in one issue, but even more notable is the appearance of several

jaw-dropping pages of comics-within-the-comic by the legendary Gary

Panter, whose raw, energetic drawings wind up being the only

self-expression of the otherwise silent alien Omega.

لا يوجد حالياً أي تعليق